Bok-Nam Park and Dan Miller

Adapted and re-edited by F. Hriadil

Forms are usually practiced with the body extended and “open.”

When training specifically for combat, you must “Close the Door.”

Most serious Pa Kua (Ba Gua) practitioners understand that Pa Kua Chang (Ba Gua Zhang) should be performed as if the practitioner is in combat. Body alignments and movements, speed and rhythm, focus and power should be consistent with what is required to succeed in a real fighting situation. The gap between theory and practice, between form and function, between the concept and the ability to truly utilize Pa Kua in actual martial combat, will never be bridged unless the student trains specifically and properly to develop the required fighting skills. The serious practitioner must understand that Forms Practice, which many teachers emphasize today, is only a very small part of the training that is required for effective and efficient self-defense.

Pa Kua Chang (Ba Gua Zhang) is the art of continuous change and adaptability. As a result, Pa Kua recognizes that one of the necessary ingredients for success in combat is a high level of mobility and maneuverability. Furthermore, Pa Kua understands that the key to mobility and maneuverability lies in stepping and footwork, and the key to stepping and footwork lies in the stance/posture. The Pa Kua skill of “moving with root,” of “lightning fast” movement while maintaining a solid root, can never be achieved unless the correct posture and body alignments are developed.

Because of this, there is a great deal of Stepping and Footwork practice in Pa Kua. This is done to train the Pa Kua practitioner to coordinate the body and hands with the feet in order to be able to move quickly out of danger and to maneuver to an optimum angle for attack or counter-attack. In general, proper Forms and Circle Walking Practice is good training for conditioning the body and developing the Qi (Chi) – [Refer to: “Dare We Awaken the Sleeping Dragon?“] And, though it is true that all legitimate forms are comprised of fighting movements and combinations, they are all typically performed with the body extended and “open.” This is done in order to develop the muscles, joints, ligaments, tendons, and the bones, etc. However, when training specifically for fighting, one must learn to “Close the Door” by modifying the body posture and stance to shut off an opponent’s access to one’s centerline, both above and below the waist. “Closing the Door” protects the body’s “Center Gate” (Chung Men), and covers all possible paths through which an opponent can attack.

In the Pa Kua method of Lu Shui-Tian, the general rule is:

“When practicing for health, the body is open;

when practicing for fighting, the body is closed.”

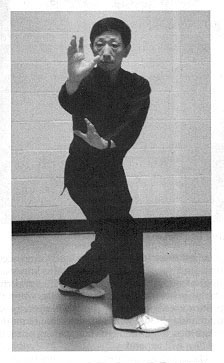

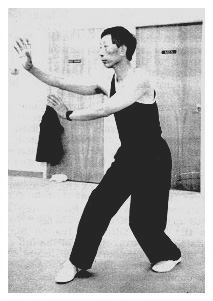

Before the student can learn proper Pa Kua Combat Stepping, however, he/she must first understand the basic Pa Kua Guard Posture/Stance. Most Pa Kua practitioners are familiar with the signature “guard” posture used in Pa Kua forms practice and Circle Walking exercises. This standard posture is shown in the picture below.

The Standard Circle Walking Posture.

- ‘In this posture, the spine is straight, the lower

- back is flat, the head is held erect, the shoulders

- are relaxed and sunk, the elbows are down, the

- arms are curved, and the knees are bent.

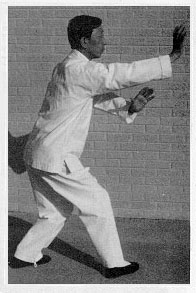

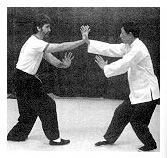

In the method of Lu Shui-Tian, the basic “guard” posture/stance that is taught for fighting is called the Dragon Posture / Stance (see picture below). It is important to note here that this posture is not just used for fighting; in the method of Lu Shui-Tian, it is also utilized for Qi Gong (Chi Kung) training as well.

The Basic Dragon Stance Combat Posture of Lu Shui-Tian

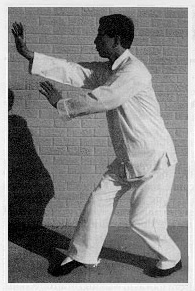

The Dragon Stance of Lu Shui-Tian is similar to the standard guard stance used in forms practice (described above); however, it differs in a few critically important areas. The weight distribution is adjusted so that approximately 40% of the weight is carried on the front leg and 60% of the weight is carried on the rear leg. Because of this, it is referred to as a 40/60 stance. The front leg and the forward foot are turned in slightly (approximately 45 degrees). And, the toes of the front foot are positioned roughly in line with the toes of the rear foot as shown below.

Foot Alignment for the

Dragon Stance

The upper body leans slightly forward from the hips, but the spine remains straight. This bending forward at the hips is traditionally called the “Tiger’s Crouch” and is utilized in a number of Chinese martial arts styles.

Both knees are bent. Bending the knees lowers the body’s center of gravity and increases stability. From this crouched position, the body is ready to move instantly in any direction. The knees should not be bent so much that the body tenses up unnaturally and feels uncomfortable. Under this condition, the body’s movement will be difficult and sluggish. And, if the body is too upright, balance will be adversely affected and speed will be hindered. When training to develop strength in the legs, low stances are necessary; however, when training for speed, the body should be at a mid-level position.

In China, when Lu Shui-Tian was young, his teacher, Li Ching-Wu, would have him stand in the back of a horse cart in the Dragon Stance/Posture. Master Li would then drive the horse cart at high speed down bumpy country roads and Lu would have to maintain his balance. In Korea, Lu Shui-Tian would require me to engage in a similar exercise by taking the bus out into the country side and back while standing in the Dragon Stance/Posture.

When assuming the Dragon Posture, two noticeable things occur. First, the knees and thighs naturally come closer together to better protect the groin area. This closes the “lower door.” Second, when the posture is correct, the hips open. Opening the hips enhances hip flexibility and facilitates ease of motion. In addition, you will notice that as the hips open, the Tan Tian expands which also facilitates Qi (Chi) manipulation and control. The Tan Tien is located a few inches below the navel within the lower abdomen. It coincides roughly with the body’s center of gravity and is believed to be the body’s central storage and distribution center for Qi (Chi). When the body’s posture is correct, the pelvic region relaxes and expands, enabling the Tan Tian to store and distribute Qi more efficiently and effectively. You can easily feel this natural relaxation and expansion of the lower abdomen by placing your hands over your Tan Tian region. Do this first while standing normally and then while sinking down into the Dragon Posture.

Both of the wrists are bent. The forward hand is held at nose level and the eyes look straight ahead through the fingers, using the space between the thumb and index finger as a “gunsight.” The lower hand is held 3″- 5″ just below the elbow of the upper arm. Holding the lower hand under the elbow of the upper arm facilitates a rounding of the back and allows the chest to relax and become empty – providing further protection to the centerline. This closes the “upper door.” Also, this posture allows the shoulders to drop or sink in a natural manner. As one assumes the proper posture, the lungs move to the rear and breathing becomes easier. The shoulders remain relaxed, the elbows are kept down, and the arms are curved. The hips are positioned naturally in alignment with the feet, with the navel and abdomen facing in approximately the same orientation as the toes. In this posture, the hands, forearms, knees, and thighs are in position to easily guard the centerline of the body with little or no wasted movement.

In most fighting situations, the opponent will already be within striking distance. The only time that a long range “Walking Step” would be used (where, for example, the back foot moves forward to become the front foot) would be when it is necessary to “close the gap” with the opponent, or to maneuver around the opponent or opponents. When the opponent is already within close range, it would be better to employ a quick and explosive step such as the “Jump Step” from the method of Lu Shui-Tian. Keep in mind that when I speak of combat here, I am not talking about the elaborate, choreographed routines you see depicted in martial arts movies or contemporary “wushu” fighting sets. These long and drawn out scenes are not realistic and are done, solely for the purpose of entertainment and/or sport. Most real fights occur at close range and are over in a matter of seconds. The “Jump Step” from the method of Lu Shui-Tian, is the best way I know of to travel a short distance rapidly with solid root and complete control. The 40/60 Dragon Stance sets up the “Jump Step” and other similar Pa Kua stepping methods. It maximizes the practitioner’s ability to move in any direction with the greatest possible speed. Maintaining a high degree of maneuverability and mobility, and a high level of speed, while travelling relatively short distances is an essential element in achieving success in combat. As stated earlier, the Pa Kua Chang practitioner relies on his/her footwork to quickly avoid attack and rapidly seek the optimum angle for counter-attack.

In the 40/60 Dragon Stance of Lu Shui-Tian, there is an automatic “spring loading” of the legs. A subtle, natural tension is set up here. This “spring loading” enables the practitioner to move forwards, backwards, or even sideways very quickly. The tension in the legs should not be forced otherwise the body will become stiff and speed will be hindered. The body should remain light and ready to move – the natural tension stemming from the posture and from the very “intention to move” itself. It enables quick and responsive movement that maximizes the mobility and maneuverability of the practitioner.

At first, the Dragon Stance posture of Lu Shui-Tian may feel a bit awkward, especially to those practitioners who do not yet have hip joints that are open and flexible. It has been my experience that most beginning practitioners are extremely tight in the hips. Nevertheless, flexibility and strength in hip movement is a key component in internal martial arts practice. Working to achieve the correct body alignment and weight distribution in the 40/60 Dragon Stance posture, along with practicing stepping methods such as the “Eight Direction Rooted Stepping” exercise [Refer to: “Martial Balance Through Ba Feng Gen Bu (Eight Direction Rooted Stepping)”], will greatly increase hip flexibility and strength as well as improve speed, agility, body control, and root. When the posture is correct and the hips are open, the Tan Tian will expand naturally and the Qi (Chi) will flow automatically. With good Qi control and a solid root, maximum power can be achieved in any strike.

Experienced fighters argue that having a “combat ready stance” is unrealistic because in an actual fighting situation one will likely not have the time to assume a specific “guard posture.” This is true; but, in Pa Kua, this is not what is done. Pa Kua Chang (Ba Gua Zhang) is the art of continuous change and adaptability. The Pa Kua practitioner reacts instantly, and without hesitation, when under attack. But, one cannot perform at this high level without many years of proper training and instruction.

It is extremely important to understand that all postures and stances in Pa Kua are dynamic. The Pa Kua fighter is constantly changing. But, hidden within each and every movement, within each and every change, is a structure, a posture, and a stance that maintains the integrity of a moving root. Training the basic Pa Kua Dragon Stance posture of Lu Shui-Tian with its “closed body” structure ingrains good habits in terms of framework, alignment, balance, coordination, root, and self-defense that serve the Pa Kua practitioner well in any circumstance. Every fighting situation is different; nevertheless, having a sound, automatic, and natural “closed body” structure is a great asset and benefit to any serious fighter. The more familiar the Pa Kua Chang practitioner becomes with the basic Dragon Stance posture of Lu Shui-Tian and with executing self-defense techniques from this posture, the faster, more versatile and more capable he/she will ultimately become.

In Conclusion:

- Maximum Protection

- Maximum Mobility

- Maximum Speed

- Maximum Power

The pursuit of all of these goals in Pa Kua begins with learning how to “Close the Door” through the Pa Kua Chang Dragon Stance posture of Lu Shui-Tian.

This article is an adaptation and re-editing of an article that first appeared in the “PA KUA CHANG JOURNAL,” Volume 1, No. 6, Sept/Oct 1991, which was published by High View Publications. The “Journal” is no longer being published and back issues may no longer be available